Orphism and “The Orphic Question"

Exploring Orpheus, Ritual Practices, and Orphic Literary Tradition.

Orphism is one of the most enigmatic aspects of ancient Greek religion, and I like to study it closely. The "Orphic Question" describes the debates between scholars trying to figure out its origins and essence. In this post, I'll discuss Orphism, the ritual practice, and the literary tradition so that you may better understand the "Orphic Question."

Orphism

Modern scholars use the term Orphism to identify a religious movement in ancient Greece that ascribed various religious rites and texts to Orpheus. Its exact nature and existence have been the subject of scholarly debate. One of the earliest scholarly opinions on Orphism comes from Proclus in the 5th century CE, who claimed that all Greek theology springs from Orphic mythical doctrine.

The scholarly debate surrounding Orphism is primarily because it differentiates itself from mainstream/public ancient Greek religion and focuses on specific beliefs and practices, such as the importance of texts, esoteric knowledge, and telestic rituals. Such ritual practices are often associated with purification and the afterlife, as reflected in the Orphic gold tablets. These tablets, discovered in graves, contain inscriptions that guide the dead in the afterlife, suggesting a belief in an esoteric knowledge that could influence one’s fate after death. The telestic practices are distinct from the literary activities of later Orphic poets, who composed hymns and theogonies (accounts of the Gods' origins). The literary tradition will be the primary focus of this post.

Orpheus

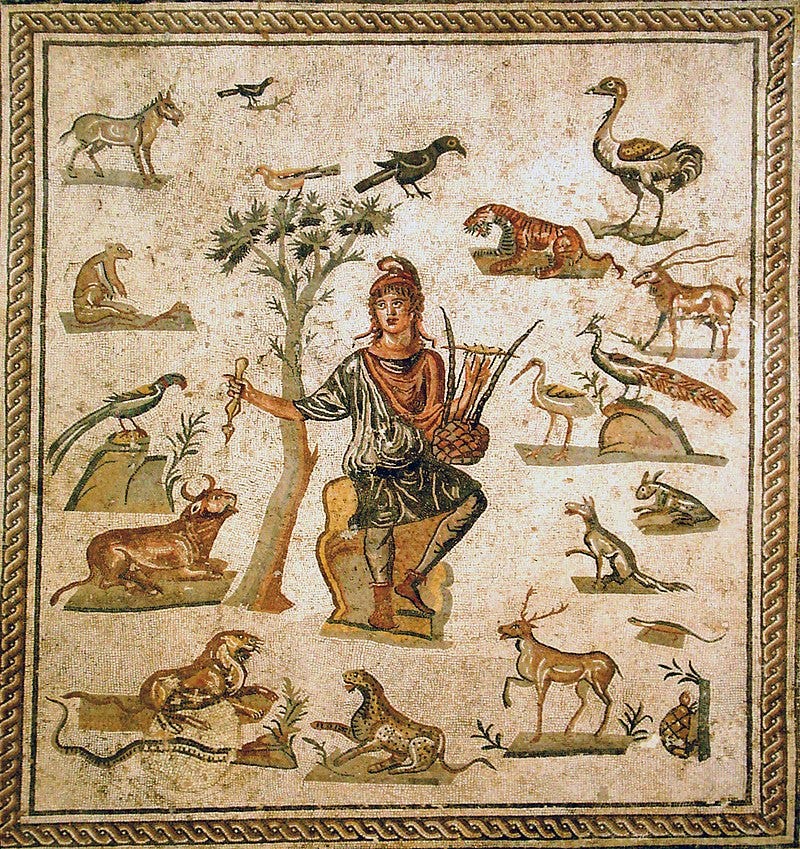

The poet-hero Orpheus is renowned in Greek mythology for his musical abilities and occupies a central place in Greek religion as the founder of the Orphic Mysteries. He could charm animals, trees, and even the Gods with his lyre. It is said that Orpheus received his lyre from Apollo, who also taught him how to play it. The lyre became Orpheus's most iconic attribute. This divine gift is a key element of the stories surrounding Orpheus, including his journey to the underworld (katabasis) to rescue his wife, Eurydice. This descent became the foundation of his legendary status and established his association with the mysteries of the afterlife and his role as a cultural hero in the Greek religious imagination.

Orphic Ritual Practices & Literary Tradition

The rituals attributed to Orpheus are as intriguing as the myths themselves. These rituals were believed to offer initiates special knowledge and purification, potentially leading to a better afterlife. However, the exact nature of these practices and their relation to mainstream/public Greek religion remain debated among scholars. Unlike the mystery rites of the Eleusis, Orphic rituals have been more diverse and individualized, possibly involving secret knowledge and texts ascribed to Orpheus.

The literary tradition of Orphism is rich and varied, embracing many texts, including hymns, theogonies, and eschatological poems. Their origin was often ascribed to Orpheus to lend them authority, and they were characterized by themes that differed from the mainstream or public Greek tradition. Some representative texts are the Orphic Hymns, the Orphic Argonautica, and various theogonies recounting the genealogies of the Gods.

The Theogonic Texts

The theogonic texts are central in the Orphic corpus. They narrate the origins of the cosmos and the Gods. They are often more elaborate and esoteric than Hesiod's "Theogony" and present a more complex cosmogony. There are four theogonies: Derveni, Eudemian, Hieronyman, and Rhapsodic.

The Derveni Theogony

One of the oldest and most fascinating texts of Orphic literature, the Derveni Theogony, is found in the Derveni Papyrus, which dates back to the 4th century BCE. It stands out for its integrations of Presocratic philosophical insights into its interpretation of creation.

The theogony begins with the primordial cosmos represented as an egg, from which the God Phanes emerges. Phanes, also known as Protogonos (the First-Born), is a central figure, symbolizing the manifestation of light and life in the universe. A central myth within this tradition involves Zeus swallowing Phanes and incorporating his powers. This profound act signifies the birth of a new cosmic order. It symbolizes renewal and the cyclical nature of existence, emphasizing the themes of unity and transformation inherent in Orphic cosmogony.

The Eudemian Theogony

Attributed to Eudemus, a student of Aristotle, adds another dimension to Orphic cosmogony. Known primarily through references in philosophical texts, this theogony provides insights into early Orphic poetry. It features a sequence of primordial Gods, often beginning with Night (Nyx) or Chronos (Time) and leading to the birth of Phanes or other primordial beings. These references highlight the intersection of Orphic myth with early Greek philosophy, illustrating how these myths were interpreted and incorporated into the broader philosophical discourses of the time.

The Hieronyman Theogony

This theogony, preserved in fragments, dates to the Hellenistic period and is named after two obscure authors, Hieronymus and Hellanicus. It begins with primordial deities like Chronos, who generates Phanes and other Gods. Similar to other Orphic theogonies, it includes a succession myth emphasizing the cyclical transfer of power among the Gods, culminating in the reign of Zeus.

The Rhapsodic Theogony

Of all the theogonic texts, the Rhapsodic Theogony is the most extensive and elaborate. Believed to be a compilation of earlier theogonic traditions, it is structured as a series of 24 books or rhapsodies. The Rhapsodies present a comprehensive account of the creation and organization of the cosmos, starting from the primordial void to the establishment of the Olympian order. The text elaborates on the birth and role of Phanes, often depicting him as the progenitor of the Gods, with his emergence from the cosmic egg and subsequent interactions with other deities forming a central part of the narrative. One of the most significant episodes in the Rhapsodies is the myth of Dionysus Zagreus. The Titans lure, dismember, and consume Dionysus, but he is later resurrected by Zeus, symbolizing themes of death, rebirth, and the eternal cycle of life. The association of Dionysus with eschatological beliefs reiterates the Orphic concerns with the afterlife, the soul, and its journey. The Rhapsodies also emphasizes Zeus’ role as the ultimate creator and organizer of the cosmos. After swallowing Phanes, Zeus recreates the universe, reaffirming his position as the supreme deity.

The Scholarly Debate

Orphism is one of the most debated topics in the study of ancient Greek religion. Questions concerning it have become known as the “Orphic Question.” The question involves the debate about what Orphism is, whether it existed at all, and what exactly it stood for. Several issues have divided scholars and produced ongoing discourse. The main points of contention include whether Orphism was a unified religious movement, the role of Orphic texts and rituals, and the doctrinal content of Orphism. Early scholars argued for a coherent Orphic community, while skeptics denied this. Recent scholarship highlights the diversity of Orphic practices and texts, suggesting a more complex picture.

Friedrich Creuzer and Christian August Lobeck started the debate in the 1820s. Creuzer saw Orpheus as a transformative figure who introduced major religious innovations to Greek religion. In contrast, Lobeck viewed Orphism as primarily a literary tradition without a unified set of religious practices or a coherent community. This fundamental disagreement set the stage for subsequent scholarly divisions in the 20th century between those who viewed Orphism as a significant religious movement (known as PanOrphists) and those who saw it as a more diffuse collection of texts and rituals without a unified community (known as Orpheoskeptics).

PanOrphists, such as Otto Kern and Vittorio D. Macchioro, argued that Orphism was a distinct religious movement with specific doctrines and practices. Kern saw Orpheus as a prophet, while Macchioro likened Orphism to early Christian communities. In contrast, Orpheoskeptics like Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff and Ivan Linforth denied the existence of a coherent Orphic community. Linforth’s “The Arts of Orpheus” argued that “Orphic” referred strictly to a literary tradition and dismissed the idea of a unified religious community.

Modern scholarship has moved the conversation beyond the strict dichotomy of PanOrphism versus Orpheoskepticism by recognizing the variety of Orphic practices without necessarily reducing them to a monolithic religion. Scholars like Fritz Graf and Sarah Iles Johnston argue that while Orphism did not constitute a unified movement, some groups and people practiced rituals and followed beliefs that can be labeled as Orphic.

Alberto Bernabé focuses on the doctrinal aspects of Orphism. Identifying the reoccurring cosmogony, eschatology, and anthropogony in Orphic texts, Bernabé argues that while Orphism may not have been a unified movement, it did have a distinct set of beliefs and practices that set it apart from other religious traditions. Bernabé cites the Orphic gold tablets, the Derveni Papyrus, and other archaeological finds as evidence of Orphic doctrines and rituals, even if practiced in different forms and local varieties.

On the other hand, Radcliffe Edmonds takes a more skeptical approach, arguing that Orphism should not be viewed as an “exception” to the general rule that ancient religions were more about rituals and myths than systematic beliefs. He proposes a “polythetic” definition of Orphism, which relies on a loose collection of features rather than a fixed set of doctrines. According to Edmonds, ancient authors labeled a text or practice as Orphic due to its extraordinary nature, antiquity, or claims to special divine knowledge rather than because it belonged to a specific religious sect.

The debate over Orphism is a fun one indeed, at least to me. I see the appeal of Fritz Graf's and Sarah Iles Johnston's middle-ground approach. Edmonds’ observation that ancient religions were more about rituals and myths than systematic beliefs is also an important reminder. I hope this post was insightful to you and leads you to explore Orphism more.