The Ethnocentric Violence of Translation: Hellenismos in Julian's Letter to Arsacius

How a 20th-Century Mistranslation of Ἑλληνισμός Shaped the Modern Reception and Misunderstanding of Julian’s Cultural Program in Modern Paganism

Hello reader, it has been a while since my last post. I’ve found it difficult to concentrate amidst ongoing world events. But I’m slowly finding my way back to productive work. On that note, I’m happy to share that I recently recorded the next guest interview for the podcast. I had the pleasure of speaking with Sasha Chaitow, which I look forward to sharing soon. Go check out her Substack Thyrathen after you are done reading my post.

Today’s post takes up an urgent and often misunderstood topic: the translation of Hellenismos in a letter by Emperor Julian to the high priest Arsacius of Galatia. Specifically, I want to address how rendering Hellenismos as “Hellenic religion” has contributed to a serious misreading of the term, one that continues to shape how modern Pagan communities define and appropriate the concept of Hellenism in problematic ways.

The motivation to write this came while reading Sasha Chaitow’s translation and commentary on the Hieroglyphica. In it, she touches on ideas from translation theory that highlight the inherently ideological nature of translation. One passage, cited from The Translator’s Invisibility by Lawrence Venuti, struck me in particular:

Translation is … a rewriting of an original text. All rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics and as such manipulate literature to function in a given society in a given way. Rewriting is manipulation, undertaken in the service of power, and in its positive aspect can help in the evolution of a literature and a society. Rewritings can introduce new concepts, new genres, new devices… literary innovation, of the shaping power of one culture upon another. But rewriting can also repress innovation, distort and contain. (Susan Bassnett & André Lefevere eds., in Lawrence Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation, New York, Routledge, 1995; Taylor and Francis 2004, viii.)

In other words, every translation reflects the translator’s choices and the society they live in. The way in which Ἑλληνισμὸς has been translated by past translators reflect their choices, which were shaped by their society, values, expectations, in the process, it distorts the original, shaping it to serve certain powers or beliefs. In Julian’s context, Ἑλληνισμός does not refer to religion in the modern sense, but rather to the entirety of the Hellenic cultural, philosophical, and civic tradition, rooted in ancestral custom, paideia, theurgy, and divine imitation, but this complexity is completely lost in translation.

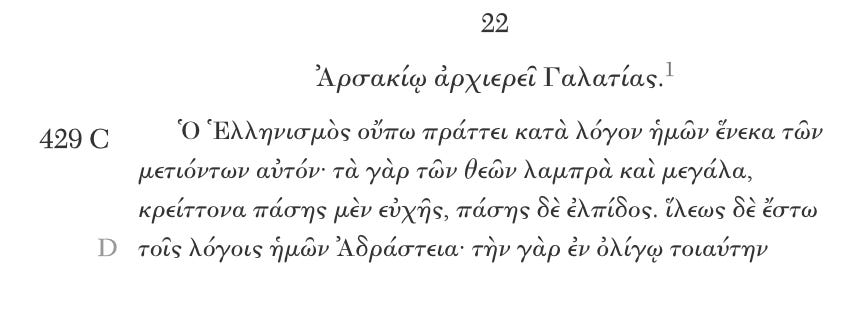

Ἑλληνισμὸς appears only once in Emperor Julian's surviving writings, in a letter urging Arsacius to reinforce the customs and values of the ancient tradition.The letter opens as follows in Greek:

Ὁ Ἑλληνισμὸς οὔπω πράττει κατὰ λόγον ἡμῶν ἕνεκα τῶν μετιόντων αὐτόν· τὰ γὰρ τῶν θεῶν λαμπρὰ καὶ μεγάλα, κρείττονα πάσης μὲν εὐχῆς, πάσης δὲ ἐλπίδος.

The commonly cited 1913 Loeb Classical Library translation by Emily Wilmer Cave Wright renders this line as:

The Hellenic religion does not yet prosper as I desire, and it is the fault of those who profess it; for the worship of the gods is on a splendid and magnificent scale, surpassing every prayer and every hope.

An alternative translation similarly reads: “The religion of the Greeks does not yet prosper as I would wish...” In both cases, Ἑλληνισμός is translated narrowly as a religion, thus reducing the depth of meaning found in Ἑλληνισμός. This has done much damage through the reception of such translations by Pagans. It serves as a primary point of ‘evidence’ that Pagans use to argue that Hellenism was a religion then and is a religion now. In Julian's Neoplatonic and civic context, Ἑλληνισμός encompasses far more than ritual/religious praxis. It refers to a whole civilizational and philosophical orientation. To reduce that nuance to a single modern category like “religion” distorts the term’s function and meaning.

This kind of distortion has real consequences, within academia and but more so outside. Outside of academia, many contemporary Pagans point to such translations as proof that Hellenism was, and is, a religion, one they can now reconstruct, adopt, or confess to believe in. But this relies on a conceptual framework foreign to Julian’s world. The error arises, in part, from a misunderstanding of how translation actually works. It’s not a mechanical substitution of words, but an interpretive act. Translators do not passively convey meaning between languages. They actively reshape meaning in ways that reflect their own assumptions and the cultural norms of their audience.

This is precisely what happened in Wright’s 1913 rendering. Her use of “Hellenic religion” reflects early 20th-century British assumptions about religion as a discrete, institutionally defined phenomenon; a product of Protestant-influenced categories. It presents Julian’s project in terms familiar to her readership, but in doing so, it imposes a modern religious framework on a term that never meant that.

Venuti calls this kind of erasure “domestication”, when a translator smooths over cultural differences to make a text more comfortable for the target audience. In doing so, the translator disappears, but so does the source culture. Venuti calls this a form of "ethnocentric violence," where the translator’s worldview overwrites the foreignness of a text. To resist this, Venuti promotes “foreignization,” which preserves the strangeness of the original text.

A foreignizing translation of Julian’s letter would transliterate Ἑλληνισμός as Hellenismos and explain its meaning through commentary: that it refers to the Hellenic mode of being, not a religion. Julian himself supports this reading. After referencing Hellenismos, he pivots to a new subject: ta tōn theōn (τὰ τῶν θεῶν), "the things of the Gods", to speak more directly of religious matters. In Julian’s vocabulary, and the broader context of Late Antique Platonism, τὰ τῶν θεῶν refers to religious matters writ large: sacred rites, divine mysteries, theurgy, sacrifices, and all that properly belongs to the Gods. These are treated as distinct from Hellenismos. By translating Hellenismos as "Hellenic religion," modern translators collapse that distinction and obscure Julian's intent.

In short, rendering Ἑλληνισμός as “Hellenic religion” is not only incorrect; it reflects and reinforces a modern ideological bias. It reshapes Julian’s intellectual world into something more familiar but far less accurate. When modern Pagan communities adopt this mistranslation as a foundation for their identity, they unknowingly inherit that distortion. A more faithful approach would respect the complexity of Julian’s language and preserve the conceptual difference of Hellenismos as something irreducible to modern categories.

The takeaway in all this is that Ἑλληνισμός is better understood as being Greek in the fullest cultural, philosophical, and spiritual sense, which includes speaking the language, studying the texts, cultivating the virtues, honoring the Gods, and participating in a cosmic order governed by logos. It is a way of life rooted in a particular cultural historical context. When Julian says that Hellenism is not acting according to reason, he is not saying a religion is broken. He is saying the entire cultural tradition has been disrupted by those who do not live in accordance with divine reason. The rites, the mysteries, the Gods themselves, are still what they always were, magnificent.

Thanks for this interesting research. A lot of this must be down, as you say, to the Enlightenment project of disembedding religion from culture (although it's not a Protestant thing - the most famous example is the attempted reinvention by Jewish reformers of Judaism as a "religion" separate from an ethnic tradition).

The thing that strikes me here is that "Hellenic" terminology was used by mediaeval Greek Orthodox Christians to describe pre-Christian polytheism and attempts to revive it. From memory, you find this in the Synodikon of Orthodoxy, and the same language was used by Patriarch Gennadios in his letter on the case of Iouvenalios which I posted about a few weeks ago. There was evidently a convention of describing pre-Christian polytheism as "Greek", even among people who were themselves (Christian) Greeks.

Not that modern "Hellenismos" would know about this - it's much more likely that they got it from the translation of Julian - but it introduces an odd complication.